Retinal Exam

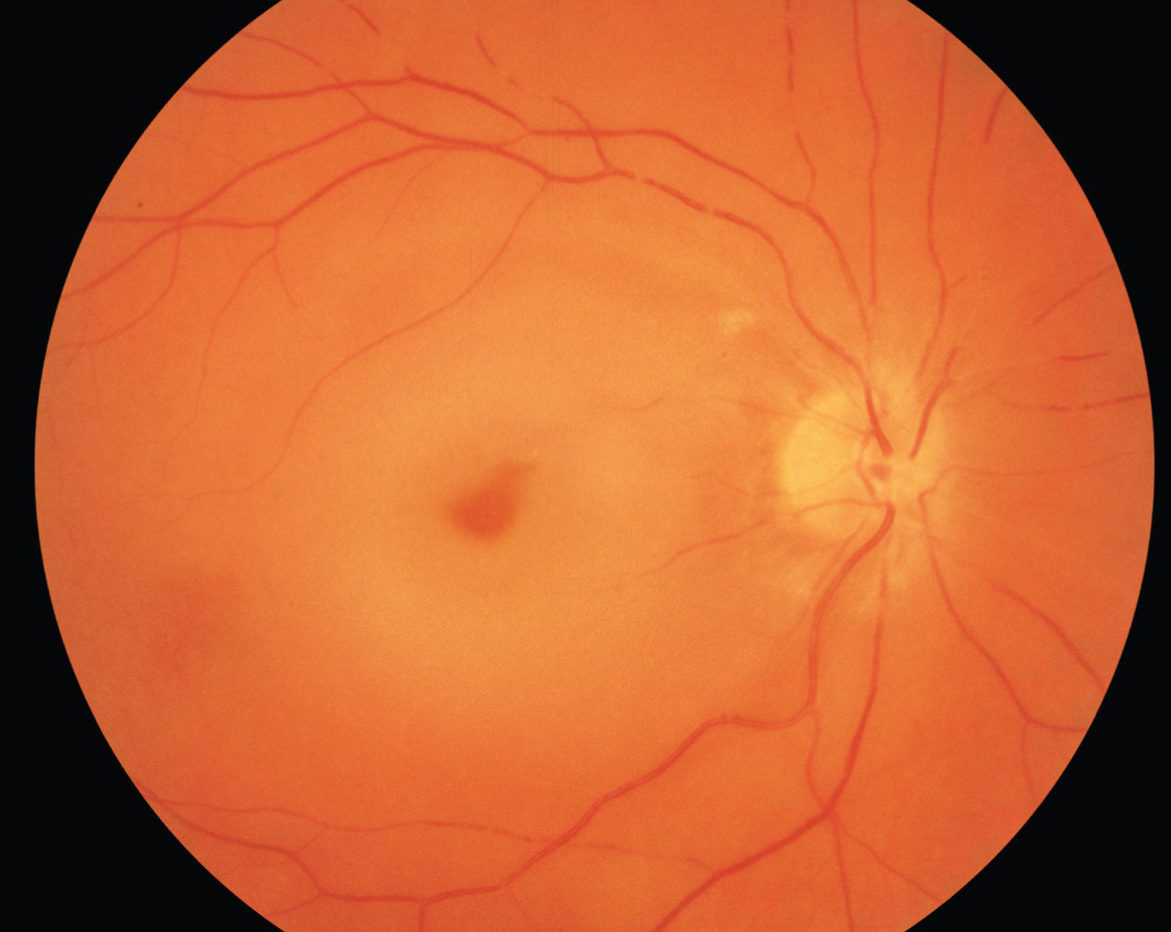

CRAO / BRAO

Most people know that high blood pressure and other heart diseases pose risks to your overall health, but many do not know that that high blood pressure can affect vision by damaging the arteries in the eye. A retinal exam can identify an RAO resulting from these blood pressure issues.

A Retinal Artery Occlusion (RAO) is a blockage in one or more of the arteries of your retina. The blockage is caused by a clot or occlusion in an artery, or a build-up of cholesterol in an artery. This is similar to a stroke.

There are two types of RAOs:

- Branch Retinal Artery Occlusion (BRAO) blocks the small arteries in your retina.

- Central Retinal Artery Occlusion (CRAO) is a blockage in the central artery in your retina.

Symptoms and Risk of a Retinal Artery Occlusion

The most common symptom of a Retinal Artery Occlusion (RAO) is sudden, painless vision loss. It can affect all of one eye, in the case of a Central Retinal Artery Occlusion (CRAO), or it can affect part of one eye, in the case of branch Retinal Artery Occlusion (BRAO). Other symptoms include:

Move the medical help instruction underneath the three symptoms.

- loss of peripheral vision

- distorted vision, and

- blind spots

Who Is At Risk for a Retinal Artery Occlusion (RAO)?

Men are more likely to have an RAO than women. The disease is most commonly found in people in their '60s. Having certain diseases increases your risk of RAO. These include:

- cardiovascular disease;

- diabetes;

- high cholesterol;

- high blood pressure; and

- narrowing of the carotid arteries.

Diagnosis of a Retinal Artery Occlusion

If you experience sudden vision loss, you should contact your ophthalmologist immediately for a retinal exam. He or she will conduct a thorough examination to determine if you have had a retinal artery occlusion. Your ophthalmologist will dilate your eyes with dilating drops. This will allow him or her to examine the retina for signs of damage.

Other tests your ophthalmologist may do are:

- Fluorescein angiography. This imaging test uses a special camera to take photographs of the retina. A small amount of yellow dye (fluorescein) is injected into a vein in your arm. The photographs of fluorescein dye traveling throughout the retinal arteries show how many arteries are closed;

- Intraocular pressure;

- Reflexes of your pupil;

- Other photos of the retina;

- A slit-lamp examination;

- Testing of side vision (visual field examination); and

- Visual acuity (sharpness), to determine how well you can read an eye chart.

Treatment of a Retinal Artery Occlusion

Several treatments may be tried but none have ever been proven to help consistently. These treatments must be given within a few hours after symptoms begin to be helpful. Some patients regain vision after a retinal artery occlusion, although vision is often not as good as it was before. In some cases, vision loss can be permanent.

Treatments include:

- Breathing in (inhaling) a carbon dioxide-oxygen mixture. This treatment causes the arteries of the retina to widen (dilate);

- Removing some liquid from the eye to allow the clot to move away from the retina;

- A clot-busting drug

What causes CRVO?

CRVO happens when a blood clot blocks the flow of blood through the retina’s main vein. Disease can make the walls of your arteries more narrow, which can lead to CRVO.

How is CRVO treated?

The blocked vein in CRVO cannot be unblocked. The main goal of treatment is to keep your vision stable. This is usually done by sealing off any leaking blood vessels in the retina. This helps prevent further swelling of the macula. Your ophthalmologist may treat your CRVO with medication injections in the eye called “anti-VEGF injections.” The medicine can help reduce the swelling of the macula. Sometimes steroid medicine may be injected into the eye to help treat the swelling. If your CRVO is very severe, your ophthalmologist may do a form of laser surgery.

This is called Panretinal Photocoagulation (PRP). A laser is used to make tiny burns to areas of the retina. This helps lower the chance of bleeding in the eye and keeps eye pressure from rising too much. It usually takes a few months after treatment before you notice your vision improving. While most people see some improvement in their vision, some people won’t have any improvement.

Central Retinal Vein Occlusion

Arteries and veins carry blood throughout your body, including your eyes. The eye’s retina has one main artery and one main vein. When the main retinal vein becomes blocked, it is called Central Retinal Vein Occlusion (CRVO).

When the vein is blocked, blood and fluid spills out into the retina. The macula can swell from this fluid, affecting your central vision. Eventually, without blood circulation, nerve cells in the eye can die and you can lose more vision. A retinal exam is required in order to make sure that there is a proper bloodflow in your eyes.

What are symptoms of CRVO?

The most common symptom of CRVO is vision loss or blurry vision in part or all of one eye. It can happen suddenly or become worse over several hours or days. Sometimes, you can lose all vision suddenly. You may notice floaters. These are dark spots, lines or squiggles in your vision.

These are shadows from tiny clumps of blood leaking into the vitreous from retinal vessels. In some more severe cases of CRVO, you may feel pain and pressure in the affected eye. CRVO almost always happens only in one eye.

Who is at risk for CRVO?

CRVO usually happens in people who are aged 50 and older, and a retinal exam is recommended for anyone in this demographic.

People who have the following health problems have a greater risk of CRVO:

- high blood pressure

- diabetes

- glaucoma

- hardening of the arteries (called arteriosclerosis)

To lower your risk for CRVO, you should do the following:

- eat a low-fat diet

- get regular exercise

- maintain an ideal weight

- don’t smoke

Your ophthalmologist will widen (dilate) your pupil with eye drops and check your retina. They may do a test called fluorescein angiography. Yellow dye (called fluorescein) is injected into a vein, usually in your arm. The dye travels through your blood vessels. A special camera takes photos of your retina as the dye travels throughout the vessels. This test shows if any retinal blood vessels are blocked. Also, your blood sugar and cholesterol levels may be tested. People under the age of 40 with BRVO may be tested to look for a problem with their blood clotting or thickening.

Your ophthalmologist may also choose to treat your BRVO with medication injections in the eye. The medicine can help reduce the swelling of the macula. These injections are a type of medicine called “anti-VEGF.” They can improve vision in about 1 of 2 patients who take them. Injections need to be given regularly for one to two years for the benefit to last. It usually takes a few months before you notice your vision improving after treatment. While most people see some improvement in their vision, some people won’t have any improvement.

Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion

Arteries and veins carry blood throughout your body, including your eyes. The eye’s retina has one main artery and one main vein. When branches of the retinal vein become blocked, it is called Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion (BRVO). When the vein is blocked, blood and fluid spills out into the retina. The macula can swell from this fluid, affecting your central vision. Eventually, without blood circulation, nerve cells in the eye can die and you can lose more vision.

The most common symptom of BRVO is vision loss or blurry vision in part or all of one eye. It can happen suddenly or become worse over several hours or days. Sometimes, you can lose all vision suddenly. You may notice floaters. These are shadows from tiny clumps of blood leaking into the vitreous from retinal vessels. BRVO almost always happens only in one eye and happens in people who are aged 50 and older. If you believe you're dealing with a case of BRVO, schedule an appointment with is for a retinal exam.

People who have the following health problems have a greater risk of BRVO:

- high blood pressure

- diabetes

- hardening of the arteries (called arteriosclerosis)

To lower your risk for BRVO, you should do the following:

- eat a low-fat diet

- get regular exercise

- maintain an ideal weight

- don’t smoke

Retinal tear and retinal detachment

Usually, the vitreous moves away from the retina without causing problems. But sometimes the vitreous pulls hard enough to tear the retina in one or more places. Fluid may pass through a retinal tear, lifting the retina off the back of the eye — much as wallpaper can peel off a wall. When the retina is pulled away from the back of the eye like this, it is called a retinal detachment.

The retina does not work when it is detached and vision becomes blurry. A retinal detachment is a very serious problem that almost always causes blindness unless it is treated with retinal detachment surgery. Vitreous gel, the clear material that fills the eyeball, is attached to the retina in the back of the eye. As we get older, the vitreous may change shape, pulling away from the retina.

If the vitreous pulls a piece of the retina with it, it causes a retinal tear. Once a retinal tear occurs, vitreous fluid may seep through and lift the retina off the back wall of the eye, causing the retina to detach or pull away. Vitreous fluid normally shrinks as we age, and this usually doesn’t cause damage to the retina. However, inflammation (swelling) or nearsightedness (myopia) may cause the vitreous to pull away and result in retinal detachment. A retinal exam can identify if this detachment is a problem and what steps to take moving forward for your eye health.

People with the following conditions have an increased risk for retinal detachment:

- Nearsightedness;

- Previous cataract, glaucoma, or other eye surgery;

- Glaucoma medications that make the pupil small (like pilocarpine)

- Severe eye injury;

- Previous retinal detachment in the other eye;

- Family history of retinal detachment;

- Weak areas in the retina that can be seen by an ophthalmologist during an eye exam.

Torn retina surgery

Most retinal tears need to be treated by sealing the retina to the back wall of the eye with laser surgery or cryotherapy (a freezing treatment). Both of these procedures create a scar that helps seal the retina to the back of the eye. This prevents fluid from traveling through the tear and under the retina, which usually prevents the retina from detaching. These treatments cause little or no discomfort and may be performed in your ophthalmologist’s office.

Laser surgery (photocoagulation)

With laser surgery, your ophthalmologist uses a laser to make small burns around the retinal tear. The scarring that results seals the retina to the underlying tissue, helping to prevent a retinal detachment.

Freezing treatment (cryopexy)

Your eye surgeon uses a special freezing probe to apply intense cold and freeze the retina around the retinal tear. The result is a scar that helps secure the retina to the eye wall.

Retinal Detachment

The retina is the light-sensitive tissue lining the back of our eye. Light rays are focused onto the retina through our cornea, pupil, and lens. The retina converts the light rays into impulses that travel through the optic nerve to our brain, where they are interpreted as the images we see. A healthy, intact retina is key to clear vision.

The middle of our eye is filled with a clear gel called vitreous (vi-tree-us) that is attached to the retina. Sometimes tiny clumps of gel or cells inside the vitreous will cast shadows on the retina, and you may sometimes see small dots, specks, strings, or clouds moving in your field of vision.

These are called floaters. You can often see them when looking at a plain, light background, like a blank wall or blue sky. As we get older, the vitreous may shrink and pull on the retina. When this happens, you may notice what look like flashing lights, lightning streaks, or the sensation of seeing “stars.” These are called flashes.

If floaters and flashes sound like a familiar symptom, do not hesitate to schedule a retinal exam with us.

Know your risks. Save your sight

If you have risk factors for retinal detachment, know the warning signs and seek immediate medical attention if you have any of these signs. If you are very nearsighted or if you have a family history of retinal problems, be sure to have complete dilated eye exams on a regular basis.

And always wear protective eyewear when playing sports or engaging in any other hazardous activities. If you have a serious eye injury, see your ophthalmologist right away for an exam. Flashes and floaters in themselves are quite common and do not always mean you have a retinal tear or detachment. However, if they are suddenly more severe and you notice you are losing vision, you should call your ophthalmologist right away.

Your ophthalmologist can diagnose retinal tear or retinal detachment during an eye examination where he or she dilates (widens) the pupils of your eyes. An ultrasound of the eye may also be performed to get additional detail of the retina. Only after careful examination can your ophthalmologist tell whether a retinal tear or early retinal detachment is present.

Some retinal detachments are found during a routine eye examination.

Symptoms of a retinal tear and a retinal detachment can include the following:

- A sudden increase in size and number of floaters indicating a retinal tear may be occurring;

- A sudden appearance of flashes, which could be the first stage of a retinal tear or detachment;

- Having a shadow appear in the periphery (side) of your field of vision;

- Seeing a gray curtain moving across your field of vision;

- A sudden decrease in your vision.

Your ophthalmologist can diagnose retinal tear or retinal detachment during an retinal exam where he or she dilates (widens) the pupils of your eyes. An ultrasound of the eye may also be performed to get additional detail of the retina. Only after careful examination can your ophthalmologist tell whether a retinal tear or early retinal detachment is present.

Some retinal detachments are found during a routine eye examination. That is why it is so important to have regular eye exams. A retinal tear or a detached retina is repaired with a surgical procedure. Based on your specific condition, your ophthalmologist will discuss the type of procedure recommended and will tell you about the various risks and benefits of your treatment options.

Detached retina surgery

Almost all patients with retinal detachments must have surgery to place the retina back in its proper position. Otherwise, the retina will lose the ability to function, possibly permanently, and blindness can result. The method for fixing retinal detachment depends on the characteristics of the detachment. In each of the following methods, your ophthalmologist will locate the retinal tears and use laser surgery or cryotherapy to seal the tear.

Scleral buckle

This treatment involves placing a flexible band (scleral buckle) around the eye to counteract the force pulling the retina out of place. The ophthalmologist often drains the fluid under the detached retina, allowing the retina to settle back into its normal position against the back wall of the eye. This procedure is performed in an operating room.

Pneumatic Retinopexy

In this procedure, a gas bubble is injected into the vitreous space inside the eye in combination with laser surgery or cryotherapy. The gas bubble pushes the retinal tear into place against the back wall of the eye. Sometimes this procedure can be done in the ophthalmologist’s office. Your ophthalmologist will ask you to constantly maintain a certain head position for several days. The gas bubble will gradually disappear.

Pneumatic Rtinopexy

This surgery is commonly used to fix a retinal detachment and is performed in an operating room. The vitreous gel, which is pulling on the retina, is removed from the eye and usually replaced with a gas bubble. Sometimes an oil bubble is used (instead of a gas bubble) to keep the retina in place. Your body’s own fluids will gradually replace a gas bubble. An oil bubble will need to be removed from the eye at a later date with another surgical procedure. Sometimes vitrectomy is combined with a scleral buckle.

If a gas bubble was placed in your eye, your ophthalmologist may recommend that you keep your head in special positions for a time. Do not fly in an airplane or travel at high altitudes until you are told the gas bubble is gone. A rapid increase in altitude can cause a dangerous rise in eye pressure. With an oil bubble, it is safe to fly on an airplane. Most retinal detachment surgeries (80 to 90 percent) are successful, although a second operation is sometimes needed. Some retinal detachments cannot be fixed.

The development of scar tissue is the usual reason that a retina is not able to be fixed. If the retina cannot be reattached, the eye will continue to lose sight and ultimately become blind. After successful surgery for retinal detachment, vision may take many months to improve and, in some cases, may never return fully. Unfortunately, some patients do not recover any vision. The more severe the detachment, the less vision may return. For this reason, it is very important to see your ophthalmologist regularly or at the first sign of any trouble with your vision.

What are flashes?

Flashes can look like flashing lights or lightning streaks in your field of vision. Some people compare them to seeing “stars” after being hit on the head. You might see flashes on and off for weeks, or even months. Flashes happen when the vitreous rubs or pulls on your retina. As people age, it is common to see flashes occasionally.

Flashes and Migraines

Sometimes people have light flashes that look like jagged lines or heat waves. These can appear in one or both eyes and may last up to 20 minutes. This type of flash may be caused by a migraine. A migraine is a spasm of blood vessels in the brain.

When you get a headache after these flashes, it is called a “migraine headache.” But sometimes you only see the light flash without having a headache. This is called an “ophthalmic migraine” or “migraine without headache.”

What are floaters?

Floaters look like small specks, dots, circles, lines, or cobwebs in your field of vision. While they seem to be in front of your eye, they are floating inside. Floaters are tiny clumps of gel or cells inside the vitreous that fills your eye. What you see are the shadows these clumps cast on your retina. You usually notice floaters when looking at something plain, like a blank wall or a blue sky. As we age, our vitreous starts to thicken or shrink.

Sometimes clumps or strands form in the vitreous. If the vitreous pulls away from the back of the eye, it is called posterior vitreous detachment. Floaters usually happen with posterior vitreous detachment. They are not serious, and they tend to fade or go away over time. Severe floaters can be removed by surgery, but this is seldom necessary.

You are more likely to get floaters if you:

- are nearsighted (you need glasses to see far away)

- have had surgery for cataracts

- have had inflammation (swelling) inside the eye

When floaters and flashes are serious

Most floaters and flashes are not a problem. However, there are times when they can be signs of a serious condition. These floaters and flashes could be symptoms of a torn or detached retina. This is when the retina pulls away from the back of your eye. This is a serious condition that needs to be treated. Here is when you should call an ophthalmologist for a retinal exam right away:

- you notice a lot of new floaters

- you have a lot of flashes

- a shadow appears in your peripheral (side) vision

- a gray curtain covers part of your vision

The eye care you deserve!

Please contact us directly with any questions, comments, or scheduling inquiries you may have.

Schedule An Appointment